Climate: Most of New Zealand shares a similar, cool

climate. New Zealand’s weather mostly comes from (and is blamed

on!) Australia, but is generally cool in the regions growing

pinot noir. There are, however, many different microclimates

resulting from the varied terrain in most of the regions, as

well as some differences between the regions themselves. For

example, Central Otago is more continental as it lies quite far

inland, as opposed to the Waipara or Martinborough, which are

near the coast.

Soils: Soils are fairly similar throughout the country,

mostly alluvian. There is some calcerous soil in Waipara (Canturbury),

but otherwise not much limestone in NZ.

Vines, vine age and clones: Although there were vines in

New Zealand as early as the 19th Century, the modern wine

industry only dates from the mid- to late-1970’s, and was

initiated by a bunch of “enthusiastic amateurs.” So most NZ

pinot is from relatively young vines, and mainly is made from 3

to 8 different (mostly Dijon) clones.

Yields: Generally 2-6 tons per hectare (roughly ¾ to 2½

tons per acre), and fermentation is usually initiated with

inoculated yeasts.

Oak: Overoaking is not a significant problem; most wines

do not show a strong oak signature. Most wines are made using

only a small percentage of new oak barrels.

Maturity: Most NZ pinots age 70% in the first 3-5 years,

then plateau for considerably longer, although there are not

many old bottles around to evaluate their ultimate longevity.

Differences arise from different approaches to the winemaking,

of course, such as the amount of stem inclusion, barrel types

and aging regimens, and different levels of ripeness at harvest

(although almost all NZ pinot seems to be between 13%—14.5%

alcohol). Of course, vintage differences also exist in New

Zealand, and are perhaps a bigger factor here than in the U.S.

The wines selected for this tasting were all from 2003, which

was described as an excellent vintage across New Zealand, and

just now entering its prime drinking window.

The wines tasted represent all of the main pinot-growing regions

of New Zealand. Although the very important region of

Martinborough was not represented, the region in which

Martinborough is located, the Wairarapa, did provide one of the

wines, although perhaps not a typical one.

Carrick (Bannockburn, Central Otago):

Open nose showing good

ripeness and berry-dominated fruit. Bright berries and a bit of

stemminess, slightly sharp acids, tight structure but with nice

complex flavors, light body and high-toned style; more an

intellectual style than hedonistic. Not the typical ripe-fruit

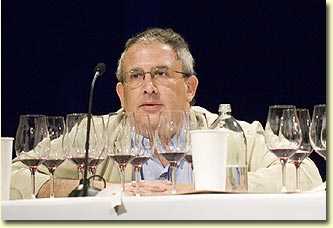

style of Central Otago. I like it, but panelist

Michel Bettane (below) calls it

“simple.”

Find this wine

Michel Bettane

Photo

Mark Coote

©

Cloudy

Bay (Marlborough)

Cloudy

Bay (Marlborough)

Closed nose with shy fruit

and some typical Pinot spice. Slightly richer than the Carrick,

but still fairly lean style of pinot with nice just-ripe cherry

fruit, light to medium bodied and good overall balance. Nice

wine if lacking much complexity. Simple (this time I agree with

Bettane).

Find this wine

Dog Point (Marlborough)

Closed nose. Much bigger and riper; thought I got a hint of TCA,

but it blew off. Ripe fruit but backed by a fairly firm

structure with strong acidity and some tannins leading to a

slightly bitter finish. Seems a bit heavy-handed and clumsy,

made in a bigger style but awkward.

Find this wine

Greenhough, “Hope Vineyard” (Nelson)

Complex nose with herbs, forest floor and spice. Round, light,

elegant, very Burgundian with forest/mushroom earthiness but

lifted by excellent acid balance; quite round, some tannins but

elegant and long. I like this one quite a bit, and I think it

has considerable potential to develop in the cellar. Bettane

call it “classic” in style.

Find this wine

Johner Estate “Gladstone Vineyard” (Wairarapa)

Slight medicinal stink (reduction or SO2?) rather like moth

balls, but this dissipates somewhat as it airs. Bright fruit

with a green tomato component. Big rich style with very good

fruit, mouthfilling, creamy with a long, clean finish, but

rather rustic and disjointed overall; unclear if it will come

together with time.

Find this wine

Mountford Estate (Waipara)

Closed nose with deeper berry fruit, some marzipan, rich and

brooding. Soft entry, fairly rich, ripe, lower acid than most,

decent balance, rather short finish. Straightforward.

Find this wine

Peregrine (Gibbston, Central Otago)

Blackberry liqueur nose, quite ripe with deep fruit, plumy. Very

ripe on the palate, rich, full bodied with some pinot spiciness;

more California-like than the others, slightly short finish.

Delicious and forward.

Find this wine

Villa Maria “Taylor’s Pass” (Marlborough)

Clean, typical pinot nose, although a bit shy. Soft, slightly

stewed quality, very ripe fruit, soft, easy, decent acid,

simple, ready to drink. Described by several panelists as a

“crowd-pleaser”, and I agree.

Find this wine

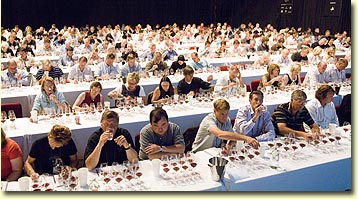

Panelists Larry McKenna, Andrew Caillard, Geoff Kelly

Photo

Mark Coote

©

The panelists

had some interesting comments on the wine, as well as the theme

of finding “typicité” and a definable terroir in New Zealand and

its various regions, and their comments reflected different ways

to think about and classify pinot noir.

Geoff Kelly (a NZ wine critic

and consultant) believes it is simply too early in NZ’s

experience with pinot to talk about region-specific terroirs. He

made an interesting point that in cooler climates, the bouquet

(with an emphasis on floral elements) is paramount when

evaluating pinot, while in warmer climates the texture becomes

the dominant factor. In the lighter, more floral wines, flavors

of strawberry, cherry and peach predominate, while the bigger,

darker wines are dominated by black cherry and dark plum

flavors. He put the Cloudy Bay, Mountford, and Villa Maria in

the lighter, red fruit camp, while the Carrick, Dogpoint,

Greenhough and Peregrine are in the darker, black fruit camp. He

described the Johner as resulting from carbonic maceration and

thus more Gamay-like (although the wine was not made by this

method). But at this point, Kelly believes the differences in

the wines span the various NZ regions and thus do not allow for

defining regional terroirs with any consistency.

Andrew Caillard, MW (a

London-based auctioneer and writer) basically agreed that it is

difficult to define terroir in NZ at this point. He described

the group of wines as a “bit of a dog’s breakfast” (i.e., a

mess), but not suffering from sameness. He likes the Central

Otago wines for their black cherry fruit, thought the Villa

Maria was a “crowd pleaser”, but criticized the Cloudy Bay and

Dogpoint (shrill, too acidic), Greenhough (loose-knit, won’t

age), and Johner (least liked of them all).

Larry McKenna (a pioneering

wine-maker in NZ) divided the wines into those that seemed to be

good examples of their respective regions (Peregrine, Cloudy

Bay, Greenhough, Mountford) versus those that emphasize the

stamp of the winemaker over the terroir (Carrick, Dogpoint,

Johner, Villa Maria). Michel Bettane (well-known French wine

critic) offered specific comments on each wine. He found the

Carrick, Cloudy Bay and Villa Maria to be too simple and lacking

complexity, although perfectly “nice” wines. He liked the

Dogpoint, Johner, and Mountford slightly more, finding them more

complex but still lacking refinement. He described the

Greenhough as “classic”, with good balance, but his favorite was

the Peregrine which he found to be perfumed, balanced and with

good length. This was surprising to me, as the Peregrine was

clearly the ripest, biggest wine, and the most “New World” in

style.

My impression was generally favorable to the wines as a group.

They clearly seem to be more in a “Burgundian” style in the

sense that there is little of the overt ripe fruit character

often seen in the bigger US pinots. The flavors have a lot more

earthy, forest-floor, herbs (but not green or vegetal), and

mineral elements and less of the ripe plum/dried fruit quality.

And the textures are lighter, more elegant, and very

food-friendly. Still, a couple of the wines were fairly ripe and

“big” in style (Peregrine, Dogpoint). And in comparing wines

within a region, there was little consistency; for example of

the two Central Otago wines, the Carrick seemed very elegant and

nuanced, while the Peregrine was much riper and more robust

(which is what Central Otago pinots are reputed to be). Few of

the wines show a great deal of complexity at this point (with

the exception of the Greenhough), and a couple were a bit rustic

or disjointed. But overall I liked the wines and suspect most

would improve somewhat with another year or two of aging. They

are made for enjoying with food, not for winning blind tastings.

A good start to the conference!

NEXT: Great Pinot

Producers

Bennett Traub

Reporting From New Zealand

Send Bennett an

Introduction |

Terroir | 8 Great Producers |

Pinots of the World |

Other Notable Pinots |

Conclusion

Cloudy

Bay (Marlborough)

Cloudy

Bay (Marlborough)