|

|

by Putnam Weekley Part I: Jargon Busting* Phenolic Ripeness * Reduction Part II: Canada Has Dugat-Py, But I'm Staying in Detroit!

Phenolic ripeness is a function of time on the vine. While some tasters

include the phrase in their notes, many instead make references to

"ripe" or "soft" or "sweet" tannins. Notes about dark color, always as a

compliment, are also a testimonial to phenolic ripeness. Color in red

wine comes from phenols. Many wines from Australia, California's central valley and, to a more

mixed degree, wines from many of the celebrated AVAs along California's

coast are both over-ripe and under-ripe: sweet, jammy, pruny, alcoholic

and permeated with flavors of green seeds and stems.

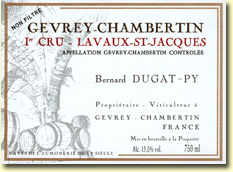

The problem with reduction is that it just can't help but sound like a good thing. Mmm: "wine" - mmm: "reduction". But reduction in wine is really a bad thing. It needs to be banished. And to do this, it needs to be understood. In a typical, randomly chosen tasting note, under "Unico 1986", temporary "reduction notes" are cited in a negative sense ("but they quickly disappear"). Yet what good is a tasting note that employs such opaque terminology? My guess is that it is being used as a euphemism. On the Novy website, to use another example, the author refers to "reduction," sprinkles some pertinent facts about it into the discussion, and misses an opportunity to make it comprehensible. Oblique references to "a somewhat unpleasant smell" make me suspicious. What is this smell and taste that cannot be named? According to Harpers, reduction is the opposite of oxidation. Insufficient oxygen in wine can lead to excessive amounts of hydrogen sulfide, a naturally occurring chemical that is also detected in aromas of band aids, masking tape, cooked veggies, canned corn, rubber and matchsticks. Some grape varieties are more "reductive" than others: Syrah is reductive; Pinot Noir and Grenache are oxidative. Considering the entire set of $10-$20 New World reds, the prevalence of reductive DMS (dimethyl sulphide) - responsible for flavors of cooked veggies and canned corn - leads me to the conclusion that reduction is rampant in our land. But this ill must be properly named to be cured. Posting tasting notes with terms like "DMS" surely won't help the average reader more than those that cite "reduction". In the most accurate sense, reduction and oxidation take place in wine all the time. They are, in themselves, value neutral. It is the excesses of oxidation and reduction that are cited by critics. The words themselves then assume the duty, aided by shadings of context, of denoting perceived flaws. Our taster of Unico 1986 (Florian Miquel Hermann) might have clarified his impressions had he detailed which sulfurous quality he detected in it. Or he might have used the taboo word "sulfur" itself. But I think he was trying to show respect for the aristocratic brand he was palate-reading. The climax of his argument appears later: "I hope the 1986 is not the signal for a change in style." "Reduction", in this case, is a malady of sophisticated wines. The Penfold's Bins 128 and 389 I've tasted over the years, on the other hand, merely tasted like "masking tape." I missed my publishing deadline for the sake of this last chapter. One week ago, while I should have been polishing up a diatribe against Pride Mountain Vineyards for these pages, I was drinking a Dugat-Py 2001 horizontal in Windsor, Ontario. This took place while gazing through a floor-to-ceiling window at the face of Detroit. Detroit was lit up orange and sunlight-yellow. The broad blue river reflected off the windowy buildings making for an image that was balanced, awe-inspiring and beckoning. In front of me were open bottles of Dugat-Py 2001 Vosne Romanee, Dugat-Py 2001 Evocelles, Dugat-Py 2001 Premier Cru, Dugat-Py 2001 Lavaux St. Jacques and Rene Leclerc 2002 Groittes Chambertin. There were four of us to share these wines. Anne was driving. Moderation be damned! Dugat-Py 2001 Vosne Romanee tasted like briary Russian forests. Arresting aromas of purple berries, sap and pepper dominated. If this was the only wine we drank that night, we'd still be talking about it. Points. Dugat-Py 2001 Evocelles was distinct. There was an entirely different chromatic theme to this wine - more saturated red and blue fruits. Anise characterized the aromas while the tannins maintained a tight, velvety grip on the finish. Many points.  I raced ahead to the Dugat-Py 2001 Lavaux St. Jacques and found the

penultimate infanticidal pleasure of my short Burgundy-drinking career.

Anne was dazzled by the decisive, very sweet truffle imprint in the

young bouquet. Blueberries, blackberries, truffles and fresh cream

characterized the mouth. It finished dry. It was fruits, cocoa and pie

spices, yet it was directed at the midpoint between sweet and savory.

Most points - 1000 points. I raced ahead to the Dugat-Py 2001 Lavaux St. Jacques and found the

penultimate infanticidal pleasure of my short Burgundy-drinking career.

Anne was dazzled by the decisive, very sweet truffle imprint in the

young bouquet. Blueberries, blackberries, truffles and fresh cream

characterized the mouth. It finished dry. It was fruits, cocoa and pie

spices, yet it was directed at the midpoint between sweet and savory.

Most points - 1000 points.Now, after the Lavaux St. Jacques, for me to patiently examine the Dugat-Py 2001 Premier Cru would be to deny the mandate of my emerging wine id, so I seized the bottle of Rene Leclerc 2002 Groittes Chambertin and poured the night's only Grand Cru into my gigantic Burgundy glass. And I was transported to California for a moment. Sure, we had all braced for an alternative interpretation of Cru Burgundy, but this was like a whole 'nother appellation! Sweet, sticky flavors of red berries, almonds, mint and ginger emerged alternately. Symmetrical and gushing with fruit, after five greedy slurps it finally showed its durable acidity, its "breeding." 821 points. By the time I got to the Dugat-Py 2001 Premier Cru I was drunk. I can hear the jeering from here. It was a fantastic wine, I'm sure of it. All the Dugats-Py were fierce, concentrated specimens, acidicly coiled with solar energy and commanding attention. Indeterminate number of points. Our host and his company are chemists. They allowed me to expertify about wine, something I do automatically and surely, at times, inappropriately. That's just how I end pregnant silences. They discussed chemistry at one point, in a way that was incomprehensible to me. But I did comprehend their interest in these wines. I know other chemists and they like wine too. My mother-in-law and stepfather-in-law are chemists and they have a big pile of full wine bottles. Chemists disproportionately like Burgundy too. As a self-regarded wine psychologist I think they are compensating. Wine, especially Burgundy wine, is the great unsolved, seductive riddle

for the chemist. See the Harpers discussion about reduction above. "More

research, please." Previously in Putnam's Monthly: Putnam Weekley's Home Page and Main Index © Putnam Weekley 2004 |

|

|