|

|

a by Putnam Weekley

The lack of reconciliation between wine professionals in their imagination of what wine is to be, often professionals within a single family, is a vein this film seeks out again and again. What is wine? Is it a consumer product or an art form? Is it an agricultural product or an archaeological artifact? Is it a drink or a religion? The film takes no final position, but its subjects do. Each answers this question uniquely.

As a consumer product, wine is in the midst of a golden age. Enabled by technology, the response time for getting precision-made wines to market is shorter than ever before in history. It is a revolution comparable to that of the microchip.

Ever since the Iron

Age the consumer market has played a decisive role in the ongoing formulation of wine. Now, however, pressures

resulting from instant communication within markets and technological

innovation in the cellar have forced all wine producers to step back,

evaluate and either change or recommit to their vision.

As one enologist's global business success attests, family values and

tradition would appear to be indecisive to the quality of wine.

Celebration of these values can be a protectionist, reactionary canard

intended to defend lousy performance, or it can be used to divert

attention away from the science of wine. Why are we tempted by appeals to individuality, tradition and culture? Are they real? Do they matter?

Two portraits in particular within Mondovino are animated by this question. Using stock cinematic narrative devices, Michael Mondavi is introduced as an evil corporate genius, while his antagonist, Aime Guibert of Daumas Gassac, is brought forward as a white hat, even if a pessimistic one (he says “wine is dead.”) Mr. Guibert would defend tradition, terroir and culture against Mondavi’s Borg-like branding machine. In this way Nossiter captures our attention with familiar storytelling figures.

But Nossiter is not content to leave it at that. In moments of unexpected candor each of them reverses these simplistic formulas. Guibert’s last shot among the vines shows him fumbling the distinction between Robert Mondavi and a group of French partners who plan a copycat venture. The camera holds on him while awkward silence clarifies his intense political motives.

In another moment of irony, Michael Mondavi defends the move to go corporate in the early nineties on emotional grounds: it meant he would get his dad back. The lump in his throat poignantly illustrates his sincerity. In contrast, his dad, Robert, claims that he got into the wine business because it is a family friendly one. Which is it? Are the wine business and family relationships good for each other or aren’t they? I’ll take Michael’s word for it.

This film is the work of a bemused skeptic, both of producers who blindly embrace technology and of dominant modern wine aesthetics. Several professional wine commentators have attempted to assassinate this work in the media only to appear jealous, incapable of tuning in the cultural diversity that wine serves to symbolize, or worse. It is an embarrassment to the professional wine writing class that Nossiter is harshly criticized for being too selective in editing his material, while James Suckling of Wine Spectator is given a pass for his imperious and trivial behavior in this film.

Recently I heard

author Ruth Reichl on the radio

comparing the odd cultural form known as the modern restaurant to a great battlefield. On

either side there is the chef and the guest. Each has an agenda and they

are often at odds. A waiter, a good waiter, is the peacemaker. So, too,

are wine producers and wine buyers often times at odds. Wine producers

want to pursue familial paradise among the quiet vines. They seek to

maximize earnings, or at least sustain their creative vision with

income. Consumers want to maximize their pleasure for the dollar and so

they apply pressure on producers to deliver more. Critics like

Robert

Parker Jr., consultants like Michel Rolland and any good merchant or

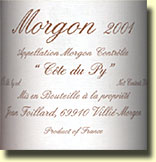

sommelier are mediators. Whose side should they be on? Any wine commentary must ultimately stand a common-sense test. How does the darn wine drink!? I place a high value on wine that not only tastes good immediately, on first encounter with it, but whose contours and complexity survive in my memory over time and with repeated exposure. For me, criticism of any particular wine is a long-term prospect. Rather than knowing thousands of different wines superficially, I choose to know a handful more deeply. Here is a sample list of specific wines appearing on my table recently which were evidently overlooked by the major critics. Each would easily rate 90-100 points in any fair use of such a scale:  Jean Foillard 2001 Morgon

"Côte du Py":

The fact that every case of this wine hasn't been gobbled up yet is a

clear indication of a particularly risky buying attitude known as

"vintage chart mentality." They say 2001 was a problematic harvest for

many Beaujolais producers. For Jean Foillard it was another notch in his

belt. I've consumed nine bottles of this wine in the last two months and

every time it outclassed other credible wines on the same table. It is

unfiltered and unsulfured. Consumers ambivalent about the merits of

Beaujolais should avoid this nervy, uncompromising expression of it at

its best. It should rest another year or two before earnest drinking of

available stocks begins. (Editor's note:

Bastardo really

likes this one too.) Jean Foillard 2001 Morgon

"Côte du Py":

The fact that every case of this wine hasn't been gobbled up yet is a

clear indication of a particularly risky buying attitude known as

"vintage chart mentality." They say 2001 was a problematic harvest for

many Beaujolais producers. For Jean Foillard it was another notch in his

belt. I've consumed nine bottles of this wine in the last two months and

every time it outclassed other credible wines on the same table. It is

unfiltered and unsulfured. Consumers ambivalent about the merits of

Beaujolais should avoid this nervy, uncompromising expression of it at

its best. It should rest another year or two before earnest drinking of

available stocks begins. (Editor's note:

Bastardo really

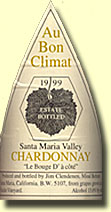

likes this one too.)Chateau Suduiraut 1964 Sauternes: I'm guilty! I paid too little for this wine - $15. But I could find nothing positive to say for it in our library of wine punditry. I relied on nothing more than the solid reputation of the producer and the good condition of the bottles to determine that I might want to drink them, even if few of my customers would. There is a bare minimum of opulent glycerin texture in it anymore. Perhaps there never was any, but the flavors are meaningful to me. A convention of nuts, honey and dried, brandied fruits meet in one's mouth with every drink.  Au Bon Climat 1999 Chardonnay, le Bouge

D' à Côté:

Winemaker

Jim Clendenen thinks he knows better than superficial market

trends and fickle professional observers what Chardonnay should taste

like. God bless him! Try tasting hundreds of soulless cookie-cutter

California Chardonnays, at all price levels, day in and day out. Observe

them age a year or two in the bottle only to wither away. Now, more than

three years after its release, this wine is hitting its stride and

promises to transform delightfully for years to come. Confronted with

such idiosyncratic raw material, most critics split the difference and

rate Jim's wines merely in the upper-good range. Are they checking their

work? A cold Santa Barbara vintage endowed this golden liquid with

insane amounts of concentrated flavors of lemon, flint and blanched

nuts. It is best when stood open for 6-24 hours and served at room

temperature. The perfect condition of the top-notch corks used in this

bottling tells volumes about who crafted it. Au Bon Climat 1999 Chardonnay, le Bouge

D' à Côté:

Winemaker

Jim Clendenen thinks he knows better than superficial market

trends and fickle professional observers what Chardonnay should taste

like. God bless him! Try tasting hundreds of soulless cookie-cutter

California Chardonnays, at all price levels, day in and day out. Observe

them age a year or two in the bottle only to wither away. Now, more than

three years after its release, this wine is hitting its stride and

promises to transform delightfully for years to come. Confronted with

such idiosyncratic raw material, most critics split the difference and

rate Jim's wines merely in the upper-good range. Are they checking their

work? A cold Santa Barbara vintage endowed this golden liquid with

insane amounts of concentrated flavors of lemon, flint and blanched

nuts. It is best when stood open for 6-24 hours and served at room

temperature. The perfect condition of the top-notch corks used in this

bottling tells volumes about who crafted it. Chateau Prieure-Lichine 1999 Margaux: This wine earned 85 points from Parker ("unsubstantial") and 82 points from Wine Spectator ("slightly diluted aftertaste.") Where does one begin to address such nonsense? This wine is actually quite dense, and though it is still in its unformed youth, it is showing clear signs of just what a magnificent, perfumed beauty it will ultimately become. Granted, to enjoy this wine currently one must suffer through expansive flavors of truffles, graphite, cocoa and sweet black berry fruits. It would be easy to name a dozen higher-scoring Bordeaux wines from the 2000 vintage that are outclassed by this gem. I blame such colossal misjudgments on the pressure to be first in the wine criticism business. Every year there is a rush to judgment and producers who bizarrely insist on "futures" commitments are equally to blame. Sometimes you don't know what a wine is going to be until you let it sit for a spell. I'm delighted to lay back and wait for the stampede to pass; it's not a bad strategy for all wine shoppers to pursue. Previously in Putnam's Monthly: Putnam Weekley's Home Page and Main Index © Putnam Weekley 2005 |

|

|